I was in Washington, D.C., in September during the week leading up to the temporarily averted government shutdown. It was fascinating. As always, it was well worth the time and effort to engage in the process. If you look past the noise and the political spin, you can see the things that you need to understand.

First of all, it’s critical to recognize that all the budget haggling in Congress is over 1/3 of the federal budget — “discretionary” spending. The other 2/3 of the budget — Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and interest on our debt — is referred to as “non-discretionary” and is not even up for discussion. Even the most conservative members of Congress will never balance the budget without tackling the “non-discretionary” piece, but the fact is neither party will touch that until they ABSOLUTELY HAVE TO. The important question is, “When will that be?”

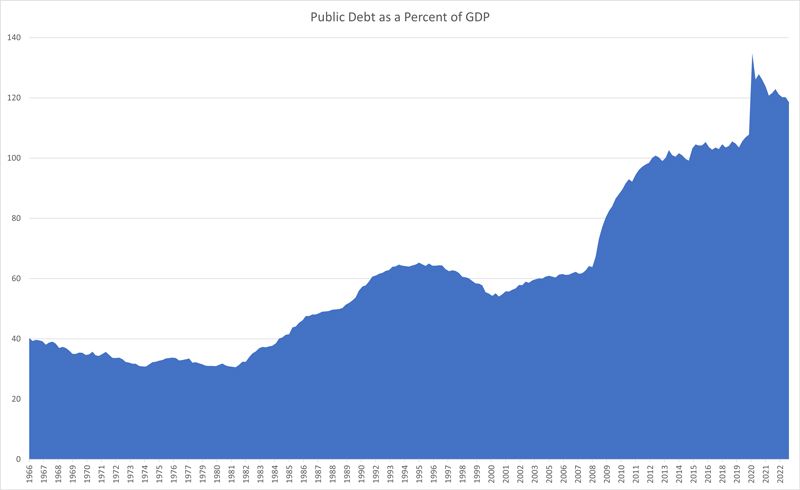

I’m afraid we won’t have the political will to address the deficit until there are no other options. And as every banker knows, that is not the ideal time to deal with problems. Markets are difficult to predict, but the time frame speeds up as the interest on our debt consumes more of the budget. And that is exacerbated as the debt increases at the same time interest rates rise. It might be five years, or 10 years, or perhaps even 50, but that time will come, and of course, that will be the absolute worst time to deal with those issues.

The bottom line is we need to start thinking and talking openly about what happens when we are no longer able to finance this recklessness. I believe this is important for two reasons. First, we need to be prepared because that’s what banks do — prepare and plan for disasters so we can be here for our customers and communities in their times of need. And secondly, if average citizens hear us and start to contemplate the inevitable pain created by this situation, voters will perhaps give members of Congress the political leeway to address “discretionary” AND “non-discretionary” spending before such a crisis occurs. As an incentive for action, I will make a bold prediction: this financial disaster will happen long before the world’s environment becomes uninhabitable.

None of this nonsensical behavior in Congress puts downward pressure on interest rates; in fact, it does the opposite. We all knew that such an extended period of abnormally low rates would have a huge impact on markets. And one of the most significant impacts might be expectations. Not only have consumers become addicted to no and low-cost debt, but Congress has as well. No one wants to make the fiscal changes necessitated by a higher interest rate environment, and this, of course, will complicate the FED’s efforts to tame inflation.

Bankers have a significant role to play. We need to give voice to the fundamental financial principles we hold dear. Unsustainable levels of debt and deficits hurt everyone, particularly future generations with no voice in today’s political debate. Expenditures must be paid for at some point. A certain amount of matching is justifiable, even prudent. Cycles of increased expenditures can be offset over time. But sustained spending beyond our ability to generate revenues or grow is reckless and constitutes the most blatant and obvious inequity on the planet — an intergenerational one.

Bankers are focused on the immediate risks that surround them, but the long-term threats of our unsustainable addiction to deficit spending, most notably inflation, are no longer beyond the horizon. Bankers can and must provide a non-political perspective that will lead us on a better path forward. To the extent it creates the will to tackle the tough issues before we absolutely must, we will all be better off.